The Magazine of The University of Montana

ALUMNI PROFILE:

A Quest For Conservation

Renowned Scientist John Seidensticker Dedicates Career to Saving Tigers

Story by Erin P. Billings

Photo by Doug Graham

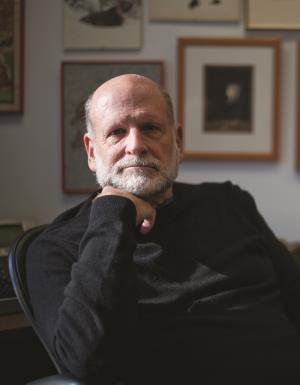

John Seidensticker in his office at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Washington, D.C.

There’s not much about John Seidensticker that doesn’t have to do with cats. Big cats, specifically. Peppering the walls of his office at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute at the National Zoo are drawings, sketches, photos, and paintings of cats. His bookshelves are flush with books about them; the table that cuts his office in half is piled high with papers, documents, and writings on them.

Maybe that’s why he’s seen as the dean of tiger biology.

Seidensticker, a conservation scientist, has come a long way from growing up and working summers on his family’s cattle ranch near Twin Bridges. He’s traveled a good part of the globe—crossing the Pacific four times last year and seven times in 2010—in the name of saving tigers.

“It was a big deal for me to leave Montana,” says Seidensticker, sixty-seven, from his cluttered office near the Adams Morgan neighborhood in Washington, D.C. “It was a big deal for me to say I wasn’t going to become a rancher. My family, being ranchers of course, they were great hunters; my grandfather and my father hunted and fished all over the world. I guess I always thought there ought to be something more than just shooting things.”

Seidensticker’s mother was a homemaker and his father a medical doctor who spent his spare time on the ranch. As it turned out, none of the Seidensticker children—there were six—pursued a career in ranching or medicine. Three became teachers, one entered pharmacy, and one became a librarian. Seidensticker chose science.

His father was demanding with high standards. Still, Seidensticker says his dad was extraordinarily supportive of his children doing what they wanted to do.

Seidensticker didn’t seem to struggle with a career choice. He enrolled as a zoology student at UM in 1963 with an eye toward conservation. It was a horizon-broadening time.

| “ | Catching my first tiger was pretty wild. | ” |

“At the University you met people who had been places,” says Seidensticker, who earned a B.A. in zoology in 1966 and an M.S. in zoology in 1968. “I was pretty parochial. I used to joke that I hadn’t been east of Hardin until I went to Asia.

“What you got from the professors at The University of Montana was this flavor that there were all these opportunities out there, that people could actually make a living being a wildlife biologist. That was a big discovery.”

An avid reader of National Geographic, Seidensticker says he knew in high school that he wanted the opportunity to work with then-Professor John Craighead after reading an article Craighead wrote with his brother, Frank, on the plight of the grizzly bear in Yellowstone National Park. The Craighead brothers spent more than a decade researching the imperiled grizzlies.

At nineteen, Seidensticker was determined to work with Craighead.

He recalls waiting in Craighead’s UM office—saying, “I got to know his office and his secretary pretty well”—until “finally John’s secretary fit me into his schedule.”

In spring 1964 Craighead offered him a job, but Seidensticker had already accepted a position at the Bureau of Land Management. So it wasn’t until the fall that he joined Craighead at the Montana Cooperative Wildlife Unit as a research assistant. In the next field season, Seidensticker joined the unit as an assistant studying the ecology of the grizzly bear.

A curious young male tiger, Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, central India, 2003

Photo by John Seidensticker

Craighead would go on to serve as an adviser for Seidensticker as he earned his master’s, but he turned into much more than that. He also was a mentor.

“John gave me five big points in life,” Seidensticker says. “Number one, don’t be afraid to take on big challenges. Two, get your science right—get your baselines right. Three, focus on the apex predators and the landscapes they need to support them. Four, communicate widely what you find. And the final thing was to have fun doing it.

“That’s what I took away from my four years under John. That’s what he did and that’s what I’ve been doing.”

Seidensticker didn’t stick with grizzlies. Traveling west to Idaho for his doctorate, his dissertation focused on mountain lions. As he was finishing up in 1973, he secured a grant, somewhat by happenstance, from the World Wildlife Fund through the Smithsonian to study tigers in Nepal. Tigers had just been declared endangered the year before.

It’s been more than thirty years, but Seidensticker’s face still lights up when he talks about the Smithsonian Nepal Tiger Ecology Project. Being in Nepal, he says, “was like being in a candy store—there were all these big mammals.”

It was very much new ground. For the first time ever, Seidensticker worked to catch tigers and leopards and put radio transmitters on them. “It was just a terrific experience,” he says. “That’s where we started.

“Catching my first tiger was pretty wild.”

Jerry Seidensticker, John’s younger brother by eleven years, traveled to Nepal on that first study. Just eighteen at the time, he remembers it as a once-in-a-lifetime experience, even though he admits he did get a little homesick. He recalls being amazed by his brother’s ability to communicate and work effectively in such a new and unfamiliar culture.

“One of the things John taught me, and it still sticks with me, is how to be patient,” says Jerry Seidensticker, principal at Rattlesnake Elementary School in Missoula. “I probably could still use some of that. I’ve always been impressed with his ability to sit back and listen to other people’s ideas. In third world countries, things move very slowly. He knew that already and had an acceptance of that.”

At that time, just one other scientific study had been conducted on tigers, so there was much that was unknown: how much area would it take to support a viable tiger population, how large was a tiger’s home range, how many animals did a tiger kill each month to survive.

“Nearly everything we knew about the natural history of tigers had been learned down the sights of a rifle,” Seidensticker says. “This was all new stuff—the fact you could catch them and follow them around and figure out what they were doing.”

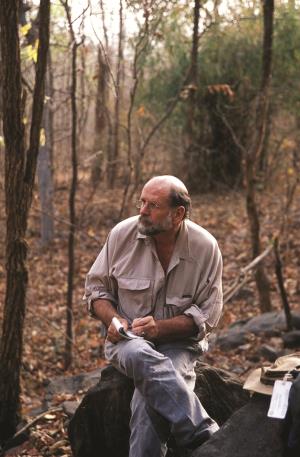

Seidensticker’s studies aren’t limited to tigers. In 2003 he and his Indian colleagues conducted a broad study of sloth bear ecology and behavior in the Panna Tiger Reserve. It was the first such study of the ant- and termite-eating bear undertaken in India’s seasonal dry forests.

Photo by K. Yoganand

Seidensticker struggles to give just one explanation for why he’s drawn to tigers. In part, he says it’s because he comes from a long line of conservationists: His grandfather was very active in ensuring the reintroduction of white-tailed deer, bighorn sheep, and turkeys. But moreover, he says he’s intrigued by how such a powerful and large animal—he recalls tracking a male tiger that was more than 500 pounds—could be so vulnerable to the threats of the human-dominated landscape that surround the few patches of natural habitat where they still live.

So he’s dedicated a large portion of his career to their protection. While at the Smithsonian—his employer for almost his entire professional life—he’s written scores of research papers, studies, and books on the subject. He’s by every measure prolific, even though he struggles with dyslexia. He thanks the spell-check on his computer for helping him deal with his disability.

Those who know him admire his tenacity and patience in a career that can challenge both.

“He’s Zen-like,” says Eric Dinerstein, chief scientist and vice president at the World Wildlife Fund, who has known Seidensticker since 1980.

“He’s very quiet; he just sits back and absorbs it all,” Dinerstein says. “Often, you will be sitting in a meeting, and he won’t say anything at all. Then, later, after he’s assessed it all, he’ll say something and very often it’s something that stops everyone in their tracks and they say, ‘Yes, that’s what we should do.’”

Joel Berger, now the John J. Craighead Chair of Wildlife Biology at UM, first met Seidensticker in 1979 while Berger was doing his postdoctorate work at the Smithsonian. He says that as a “young and impressionable scientist,” he looked up to Seidensticker.

“I thought, ‘Oh yeah, Seidensticker, he does some cool stuff in a lot of exciting places,” Berger says. “He’s somebody I think I could learn from.’”

Berger calls Seidensticker a “muddy boots-type guy” who can see both sides of the conservation equation: the animal perspective and the human perspective. And, Berger says, he has “a beautiful calmness.”

“He doesn’t have to be the guy out at the front, chest beating,” Berger says. “He has amazing patience and internal confidence.”

For all the accolades, Seidensticker is quick to credit his wife of twenty-nine years, Susan Lumpkin, with whom he has partnered on numerous projects and written and edited ten books. In many ways, as they both admit, they have shared a career. They met at the zoo when Lumpkin was a postdoctorate fellow three decades ago.

“She’s the voice. She’s the writer. She writes the poetry,” Seidensticker says.

Lumpkin recalls meeting John and says even though it took them a year or two to come together, it was “love at first sight.”

It was her first job interview at the zoo, and afterward, Seidensticker offered to walk her back to Connecticut Avenue, a major thoroughfare in D.C. Lumpkin remembers how Seidensticker took her, all dressed up and wearing heels, on a trek over a hill and through some woods to get to her destination. Since then, she says: “We’ve spent most of our lives going up and down mountains together.”

They both are involved in the Global Tiger Initiative, an alliance of governments, conservationists, and international organizations launched in 2008 to save tigers from extinction. At a summit a year ago in St. Petersburg, Russia, participants set an ambitious goal to double the world’s wild tiger population from 3,200 to 6,400 in a dozen years. Seidensticker serves as an independent adviser to the World Bank for the initiative, while Lumpkin is a consultant to the World Bank for the project. The World Bank helped start the effort and funds the Global Tiger Initiative’s secretariat.

Seidensticker calls being involved with the Global Tiger Initiative one of the most challenging times of his career.

“Most people hit sixty-five and they are ready to retire,” he says. “This is the most intense learning curve I’ve ever been on.”

Scott Derrickson, who is deputy director of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Va., and oversees the research centers at the National Zoo, including Seidensticker’s, says if the Global Tiger Initiative doesn’t work, nothing will. But his hope is that it does, and that ultimately it will define Seidensticker’s legacy.

“I’m hoping that in twenty-five or thirty years, John is known as one of the people that really helped to save tigers,” says Derrickson.

Lumpkin doesn’t pause when she talks about Seidensticker’s passion for and success at conservation biology. He is tireless, tolerant, and has an uncanny sense of landscape, which she attributes to his having grown up in Montana.

“Coming from Montana is a really powerful part of John’s being,” she says.

It’s been forty years since Seidensticker left Montana. He and Lumpkin, a Michigan native, make it a point to visit, but they never really entertained moving back for good.

“Susan and I joke that once you get warm, you can’t get cold again,” he says.

There’s no doubt Seidensticker is both comfortable and challenged at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, and he doesn’t seem to have plans to go elsewhere. Besides, he admits, he still has much more work to do to meet the goals of the Global Tiger Initiative.

Whatever lies ahead, Seidensticker is already viewed as having played a critical, if not unmatched, role in preserving and enhancing the world’s tiger population. But don’t try to give him the credit.

“There are a lot of champions,” he says. “I’m just one of the players.”

Email Article

Email Article